The Amarna Letters give us the details of ancient Egyptian diplomacy and expose how power was built, alliances were forged, and pharaohs were flattered.

Often, archaeologists are lucky enough to come across a whole collection of documents that completely transform their knowledge of an ancient period. This allows them to closely observe the time in in detail.

The treasure that transformed Egyptology is undoubtedly the Amarna Letters; 382 clay tablets considered the oldest known diplomatic documents.

These documents are correspondence written in the 14th century BC between the Pharaohs and their rival kings, the Babylonians, Assyrians, Hittites, and Mitannians, and includes letters written by the “puppet” kings under Egyptian rule.

The archive begins from the reign of Amenhotep III (1390–1353 BC), the great founding king of Egypt, and also covers the reign of his son, Akhenaten (1353–1336 BC), whose religious revolution rocked ancient Egypt for a generation.

The letters provide insight into the ancient Egypt of the 18th dynasty, offering a detailed overview of the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East in the Late Bronze Age.

Sun City

Around 1348 BC, Pharaoh Akhenaten moved his court to an isolated place further north, between Thebes (his former capital) and Memphis. The change was part of the pharaoh’s radical objective: to worship Aten, the sun, as an almost exclusive divinity of Egypt.

Akhenaten’s new capital, on the east bank of the Nile, was called Akhetaten, meaning “Aten’s horizon”, and surely alluding to the hills that framed the rising sun.

Its current name, Tell el Amarna, is also used to designate the site of Akhetaten. It also names the incredible culture that briefly flourished when the new religion (worshipping Aten) was accompanied by the rise of the revolutionary Amarna art style.

Akhenaten’s reign, however, did not involve only a religious and artistic revolution. He had inherited the powerful kingdom and prestige of his father, Amenhotep III, and continued to advocate for Egyptian interests, especially in Nubia, a region to the south where minerals were abundant.

Until the day of Akhenaten’s death in 1336 BC, the capital of ancient Egypt was a bustling city full of palaces and temples, houses, barracks, and administrative buildings. It was in these buildings that the diplomatic letters were found, beginning with those from Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye.

The ancient city was identified in Amarna in the late 1700s when the Akhetaten cairn was found there. The letters came to light in the 1880s after a series of chance finds.

As the site’s existence became known, it quickly acquired great archaeological importance. Wallis Budge, curator of the British Museum, managed to obtain a batch of 82 pieces. Through the antiquities market, many tablets also reached the Egyptian Museum (Cairo) and the Staatliche Museum (Berlin).

In the first major excavation at Amarna (1890s) by British Egyptologist William Flinders Petrie, more tablets from Akhenaten’s time were found.

During his first campaign, Petrie explored a building with the phrase “Pharaoh’s Correspondence Office” written on its bricks.

However, the letters are not written in ancient Egyptian, but in Akkadian, a language spoken in ancient Mesopotamia. In the second millennium BC, Akkadian became a lingua franca throughout the region, serving a similar role to that of English in international relations today.

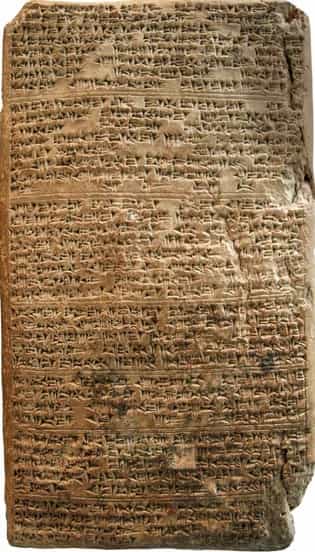

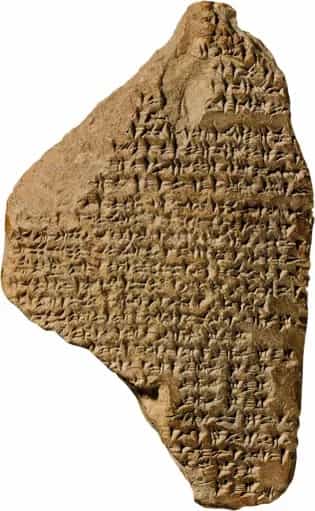

Written in the cuneiform system, most of the tablets found to date are letters received by the ancient Egyptians. Only a few copies of letters written by pharaohs were preserved.

“Puppet” king letters

Scholars have divided the Amarna Letters into two main groups. One includes letters to the pharaoh written by the leaders of states controlled by Egypt; the others are letters to the pharaoh written by his peers (or, as he would have believed, his quasi-peers), the rulers of the other independent powers.

In letters by the “puppet” kings, the writers expressed themselves with extreme servility. For example, the king of Gezer wrote:

“To the king, my lord, my god, my sun, the sun of heaven: Message from Yapahu, your servant, the earth that your feet shake. I fall at the feet of the king, my lord, my god, my sun, seven times and seven times.”

In contrast, in letters written by the pharaoh’s peers, the rulers of the great regional powers, make a judicious effort to use language that denotes equal footing.

Some of the letters date back to the reign of Amenhotep III and his great royal wife, Tiye, mother of Akhenaten. After Amenhotep’s death, Tiye remained in power when her son took the throne. Akhenaten moved his father’s archives to the new capital to record diplomatic relations with Egypt’s allies and vassal states.

Source: JOSE LULL, National Geographic

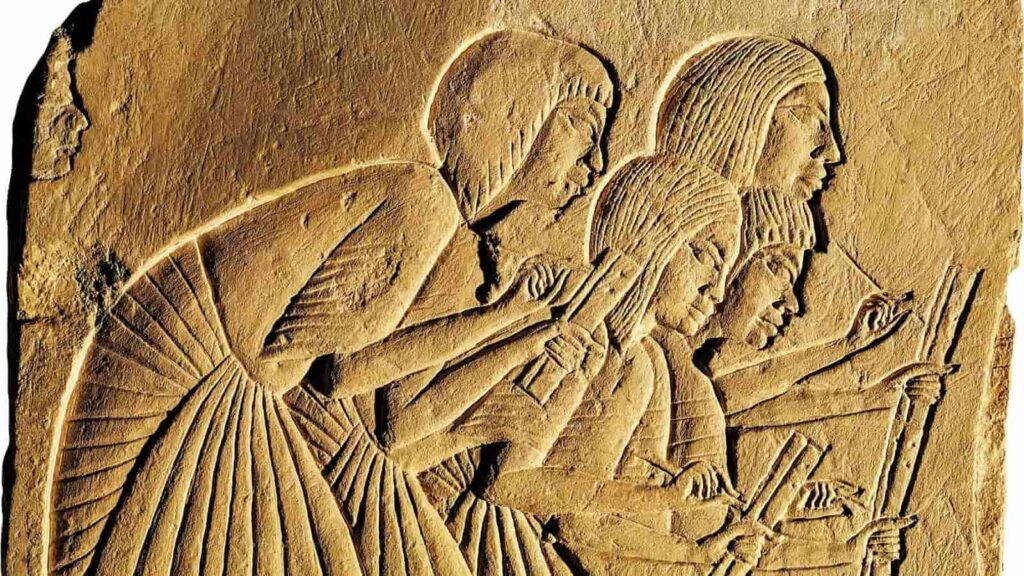

Scribes, relief from the Tomb of Horemheb, Saqqara, circa 1400 BC National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Italy. BRIDGEMAN PHOTOGRAPHY, ACI

The elaborate face on this coffin was gone when it was found in 1907 in tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings. Some inscriptions suggest that it was the face of Akhenaten. PHOTOGRAPH BY ALAIN GUILLEUX,

The sun rises behind the ruins of the Great Temple of the Aten in present-day Amarna, Egypt. Akhenaten moved the capital to this place to found his new religion. PHOTOGRAPHY BY KENNETH GARRETT

Letter 5 of Amarna Letters. british museum london. PHOTOGRAPH FROM BRITISH MUSEUM , SCALA , FLORENCE

The statues of Amenhotep III and his wife Tiye used to be the same size, indicating a more equal relationship between this pharaoh and his queen. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. PHOTOGRAPH FROM DE AGOSTINI PICTURE LIBRARY, SCALA, FLORENCE

A gold ring found at Amarna depicts Akhenaten and his queen Nefertiti. Circa 1353-1336 BC Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. PHOTOGRAPH FROM ALBUM, METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Pharaoh Akhenaten worships the sun disk, Aten. These limestone bricks, known as talatat, were built for the Temple of Aten at Karnak, but were later torn down. PHOTOGRAPHY BY KENNETH GARRETT