In a remarkable find in the heart of the nineteenth century, miners stumbled upon hundreds of stone artifacts and human remains in the tunnels of Table Mountain and other regions within the California gold mining area. Experts suggest that these bones and artifacts originated from Eocene-era strata, dating back 38 to 55 million years, according to Dr. J.D. Whitney, a prominent government geologist in California during that time.

Whitney’s insights were documented in the 1880 publication, “The Auriferous Gravels of the Sierra Nevada of California,” by Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Comparative Zoology. However, this publication was later removed from scientific discourse due to its challenge to Darwinist views on human origins. The gold rush of 1849 had initially drawn attention to the gravel deposits in the Sierra Nevada Mountains’ riverbeds, attracting adventurers to towns like Brandy City, Last Chance, and Lost Camp.

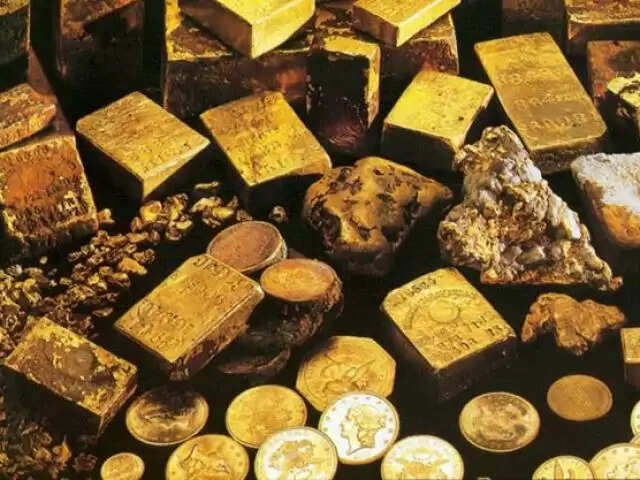

Initially, miners sifted through gravel deposits in streambeds to extract gold nuggets and flakes. As mining corporations invested more resources, they bored shafts into mountainsides, following gravel deposits wherever they led. Some utilized high-pressure water jets to clear auriferous (gold-bearing) gravels from slopes.

Among the findings were numerous stone artifacts and human bones. J.D. Whitney emphasized the importance of dating these discoveries accurately. While surface deposits and artifacts from hydraulic mining were challenging to date, those found in deeper mine shafts or tunnels could be dated more precisely. Whitney asserted that geological data indicated the auriferous rocks were at most of Pliocene age, although modern geologists believe some gravel deposits may date back to the Eocene.

The extensive mining efforts involved driving shafts deep into Table Mountain’s strata, reaching the gold-bearing rocks. Some shafts extended under the latite for hundreds of yards. Gravels on top of bedrock could be anywhere from 33.2 to 56 million years old, while others ranged from 9 to 55 million years old.

William B. Holmes, a physical anthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution, criticized Whitney’s conclusions, suggesting that he might have hesitated if he had a complete understanding of human evolution as known today.

In essence, the findings challenge the idea that facts must align with preconceived notions, a sentiment echoed in the treatment of the archaeological site of Hueyatlaco in Mexico, where stone tools near animal bones were dismissed due to conflicting timelines. The article concludes by highlighting the importance of reevaluating historical discoveries in light of evolving scientific knowledge.