Wadi al-Jarf, Egypt – The ancient papyrus scrolls discovered in the limestone caves of Wadi al-Jarf have unveiled a treasure trove of information about the daily lives of workers involved in constructing one of the world’s most iconic structures – the Great Pyramid of Giza. These remarkable findings shed light on the organization, activities, wages, and even meals of the labor force dedicated to this monumental project over four millennia ago.

About 4,500 years ago, the Great Pyramid of Giza – the leading great architectural work of ancient Egypt, was built during the reign of pharaoh Khufu. (Photo: Pinterest)

Located on Egypt’s Red Sea coast, Wadi al-Jarf emerged as a crucial hub more than 4,000 years ago, as revealed by French Egyptologist Pierre Tallet’s excavations in 2008. The site’s significance was underscored when it yielded 30 of the oldest papyri ever discovered, providing invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian history. Among these scrolls, one stands out – the diary of a man named Merer, who played a pivotal role in the construction of the Great Pyramid during the reign of Pharaoh Khufu.

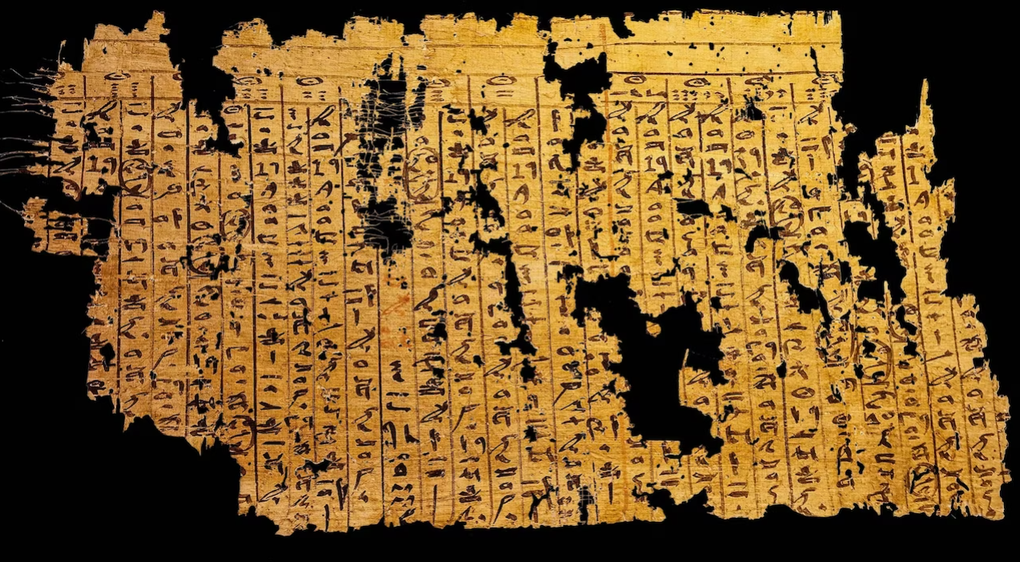

Dry conditions in Wadi al-Jarf helped preserve the Merer papyrus. Photo: Past

Stretching across several kilometers between the Nile and the Red Sea, Wadi al-Jarf was a bustling economic center with limestone caves for storage, camps, stone buildings, and a harbor. The discovery of Merer’s diary, along with other ancient documents, offers a glimpse into the vibrant activity that fueled the pyramid’s construction. Merer meticulously documented his team’s activities, including the procurement of materials like limestone from the Tura quarry and their transportation via the Nile to Giza.

Merer’s team, comprising around 200 skilled workers, played a crucial role in ferrying limestone blocks from the quarry to the pyramid site. Contrary to popular belief, these workers were not slaves but skilled laborers who received wages for their efforts. Merer’s diary provides detailed accounts of their compensation, dispelling myths surrounding the pyramid’s construction.

The papyrus scroll helps posterity better understand the process of building the Great Pyramid of Giza. (Photo: Pinterest)

Payment for labor was made in kind rather than currency, with workers receiving rations of grain flour based on their rank. Merer’s records also shed light on the workers’ diet, which consisted of yeast bread, flatbread, meats, dates, honey, beans, and beer. Such provisions highlight the organized and well-maintained workforce involved in the pyramid’s construction.

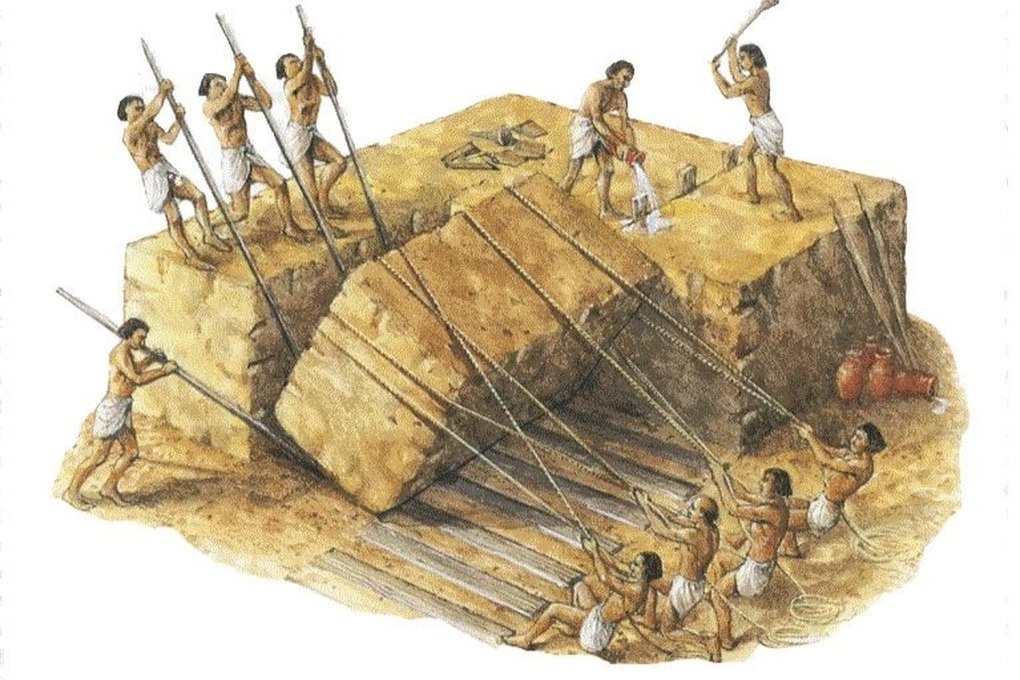

The image depicts Egyptian workers transporting stone blocks to build the pyramid (Photo: Getty).

Moreover, Merer’s diary offers insights into the hierarchy and management structure of the project. It mentions Ankhhaf, the half-brother of Pharaoh Khufu, who held authority over all royal works, including the pyramid’s construction. Merer’s meticulous documentation underscores the complexity and sophistication of ancient Egyptian society, challenging conventional assumptions about pyramid builders.

Part of Merer’s diary reveals how the Egyptians built the pyramids (Photo: National Geographic).

The discovery of Merer’s diary and other papyri at Wadi al-Jarf opens a window into the past, allowing us to unravel the mysteries surrounding one of the world’s most iconic monuments. These ancient documents not only enrich our understanding of ancient Egyptian civilization but also highlight the ingenuity and skill of the labor force behind the Great Pyramid of Giza. As researchers continue to unravel the secrets of Wadi al-Jarf, the legacy of Merer and his fellow workers continues to inspire awe and admiration for their monumental achievements.