The demand for ivory threatens to wipe out Africa’s elephants.

FRANK WEITZER/ AFRICAN PARKS

A herd of elephants roams across a grassy plain. The animals are in Malawi, a country in Africa. Above them, a man leans out of a helicopter and fires a dart gun. Darts hit the massive animals and they fall, one by one, to the ground. The elephants are knocked out but unharmed. Soon, the animals will be transported 200 miles to a new home.

This scene from last July was part of a project called 500 Elephants. The goal is to relocate 500 elephants by the end of this summer. They will be moved to a park in northern Malawi called the Nkhotakota (nik-HOH-ta-koh-ta) Wildlife Reserve. The elephants being moved there are safe from poachers who kill elephants to trade (buy and sell) their ivory tusks. The 500 Elephants team has the same goal as many other conservation groups. They want to save Africa’s elephants before the animals become extinct.

Jim McMahon/MapMan®

The End of Elephants?

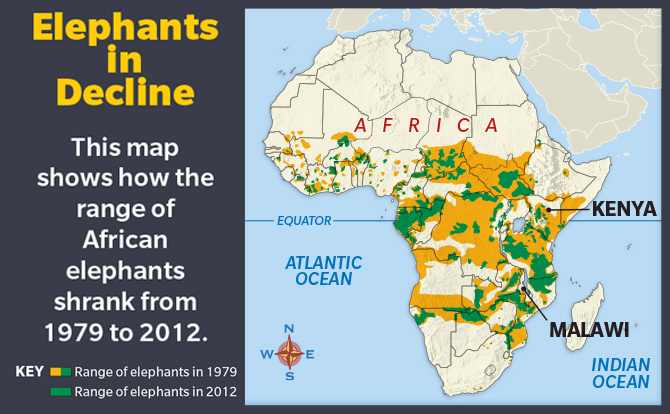

There was a time when African elephants numbered in the millions. Today, experts estimate that fewer than 500,000 are left. A survey released last August called the Great Elephant Census shows just how urgent the situation is. The number of Africa’s savanna elephants dropped by nearly one-third since 2007.

“Sadly, wherever these animals exist in the wild, they are threatened,” says Andrea Heydlauff. She works for the conservation group that started 500 Elephants.

Hunted for Ivory

To help save elephants, nations around the world made an agreement in 1989. They made it illegal to trade most ivory taken from elephants after that year. But these rules haven’t stopped poachers. Every day, about 100 elephants in Africa are still killed for their ivory tusks.

Poachers shoot or poison the elephants. Then they saw off the tusks, leaving the dead bodies behind. Most of the tusks are smuggled by ship from Africa to Asia. About 70 percent of illegal ivory ends up in China.

In China and some other countries in Asia, ivory is a symbol of wealth. It’s carved into items like jewelry, statues, and chopsticks. Some people use crushed ivory in medicines, mistakenly believing it has healing powers.

Ivory isn’t in demand only in Asia. The U.S. is the second largest market for ivory.

“Ivory is beautiful, but it comes from dead elephants,” explains James Deutsch, from the Great Elephant Census team. “Wouldn’t we rather have elephants in the world than ivory chopsticks?”

Hope for the Future

Last year, the world’s top two ivory markets agreed to work together to end the ivory trade in their countries. In July, the U.S. toughened its laws about trading ivory. Now, most ivory sold in the U.S. must be at least 100 years old—from long before elephants were at risk.

In December, China also made a huge announcement, one that many conservationists say is the biggest yet. China said it would ban the trade of all ivory by the end of this year.

Meanwhile, the elephants that were moved last summer are adjusting well to their new home. Deutsch knows that elephants still face a difficult struggle. But he’s optimistic about the future of the species.

“I think we will solve this problem eventually,” he says.

A $105 Million Fire

CARL DE SOUZA/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

One way officials try to stop poachers is by seizing, or capturing, ivory from them. Last April, officials in the African nation of Kenya burned 105 tons of seized ivory. The tusks were worth about $105 million. The ivory had been seized by authorities over several years. According to the Kenya Wildlife Service, it came from more than 8,000 elephants.

Destroying tusks may seem like a strange way to help save elephants. But it’s meant to send a message to poachers, smugglers, and anyone who buys illegal ivory.

“For us, ivory is worthless unless it is on our elephants,” said Kenya’s president.