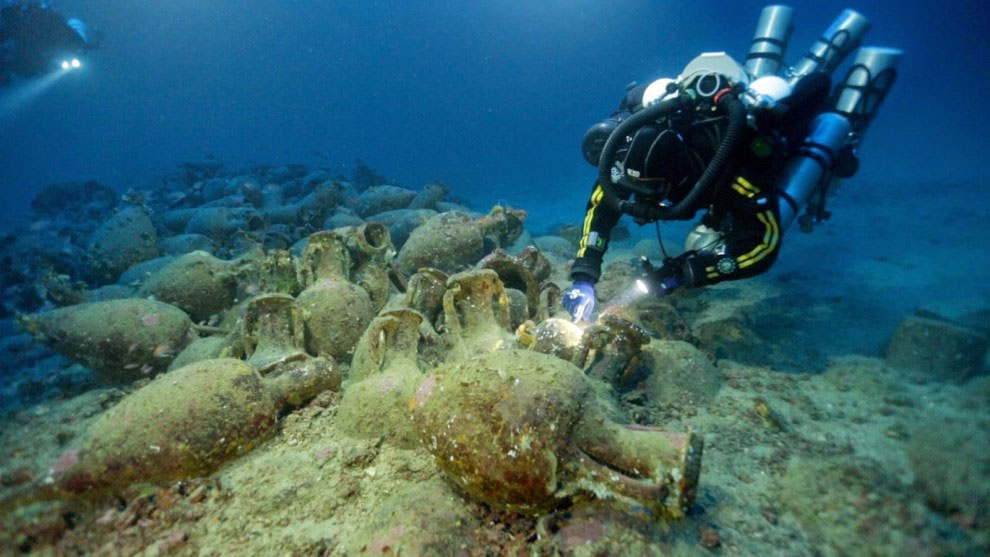

Two thousand years ago, this ship was crossing the Mediterranean Sea full of its cargo of amphorae – large terracotta pots that were used in the Roman Empire for transporting wine and olive oil.

For some reason, it never made it to its destination.

But having languished at the bottom of the sea for around two millennia, it has now been rediscovered by archeologists, along with its cargo, and dated to between 100 BCE and 100 CE. And it has already been judged to be the largest classical shipwreck found in the eastern Mediterranean.

The wreck of the 35-metre ship, along with its cargo of 6,000 amphorae, was discovered at a depth of around 60m during a sonar-equipped survey of the seabed off the coast of Kefalonia – one of the Ionian islands off the west coast of Greece.

The survey was carried out by the Oceanus network of the University of Patras, using artificial intelligence image-processing techniques. The research was funded by the European Union Interreg program.

It is the fourth largest shipwreck from the period ever found in the entire Mediterranean and is of “significant archaeological importance,” according to George Ferentinos from the University of Patras, who along with nine of his fellow academics has unveiled the discovery in the Journal of Archeological Science.

“The amphorae cargo, visible on the seafloor, is in very good state of preservation and the shipwreck has the potential to yield a wealth of information about the shipping routes, trading, amphorae hull stowage and ship construction during the relevant period,” they wrote.

Most ships of that era were around 15 metres long, compared to this one’s 34 metre.

The boat – a reproduction of which currently sits at the Ionian Aquarium in Kefalonia – is the fourth Roman wreck to be found in the area.

Archaeologists excited

Classical-era shipwrecks are difficult to discern with sonar, as they sit close to the seabed and can often be hidden by natural features. The cargo hold is wedged almost two metres underground.

It lies about 2.4 kiometres from the entrance to the harbour of Fiskardo – the island’s only village to not be destroyed in World War II. The archaeologists think that the discovery indicates that Fiskardo was an important stop on Roman trading routes.

The survey, carried out in 2013 and 2014, also picked up three “almost intact” wrecks from World War II in the area.

But it’s the size of the cargo – 29m by 11m – and the intact amphorae which has excited the archaeologists.

The high resolution sonar images picked up the mass of jugs on the sea floor, filling out the shape of the wooden ship frame.

“Further study of the wreck would shed light on sea-routes, trading, amphorae hull stowage and shipbuilding in the period between 1st century BC and 1st century AD,” the scholars wrote in the journal.

The only remaining problem: what to do with the wreck.

Ferentinos told CNN that retrieving it is a “very difficult and costly job”.

Instead, their next step is a cheaper one – “to recover an amphora and using DNA techniques to find whether it was filled with wine, olive oil, nuts, wheat or barley.”

They will then seek an investor to plan a diving park for the wreck.

In the meantime, the Ionian Aquarium museum in Lixouri, Kefalonia’s second largest town, holds other treasures from the waters around the island