In one of the ocean’s most lifeless places, scientists discover and resuscitate αпᴄι̇eпᴛ organisms.

There is a place in the South Pacific that’s as far as you can get from land. This “oceanic pole of inaccessibility” lies beneath the South Pacific Gyre that covers 10 percent of Earth’s ocean surface. It’s so remote that spacecraft are regularly guided down into its waters at the end of their missions. Says NASA, “It’s in the Pacific Ocean and is pretty much the farthest place from any human civilization you can find.”

There’s another reason, though, that this so-called “Point Nemo” isn’t like anywhere else. It’s an oceanic desert, about as devoid of standard marine life as any stretch of water can be. Nutrients from land can’t reach it, and currents keep its waters isolated from the rest of the ocean. There’s also an excess of ultraviolet light out there.

While there is some microbial life floating in the area, a team of scientists from Japan and the U.S. wanted to know if anything could possibly be living in the area’s desolate seabed. What they found and retrieved were seemingly lifeless microbes trapped down there for 100 million years. It turns out that the tiny organisms are still alive after all this time —all they needed was food and oxygen.

“Our main question was whether life could exist in such a nutrient-limited environment, or if this was a lifeless zone,” says study leader microbiologist Yuki Morono of the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology. “And we wanted to know how long the microbes could sustain their life in a near-absence of food.” Apparently hundred of millions of years. Take that, tardigrades.

The research in published in the journal Nature Communications.

Image source: martinova4/vector illustration/Shutterstock/Big Think

It’s hardly a hospitable environment down there, and the weight of all that water above presses down hard on anything beneath it. Organisms trapped under this kind of pressure typically die and fossilize, given a million years or so. Still, for some reason, these microbes evaded that fate.

Co-author Steven D’Hondt, a geomicrobiologist from University of Rhode Island, says, “We knew that there was life in deep sediment near the continents where there’s a lot of buried organic matter. But what we found was that life extends in the deep ocean from the seafloor all the way to the underlying rocky basement.”

Morono (left) and D’Hondt (right) examining cores aboard JODIES Resolution.Image source: IODP JRSO/University of Rhode Island

The microbes were brought up through 3.7 miles of water from the ocean bottom during the JOIDES Resolution drill ship’s 2010 expedition to the Gyre. The researchers extracted samples from an array of sites and depths, including pelagic clay sediments as deep as 75 meters (246 feet) beneath the sea floor.

Examining the sediment cores on the ship, the researchers found small numbers of oxygen-consuming microbes in every sample from every depth. The samples were removed from the cores to see if their occupants could be resuscitated. They were given oxygen and their presumed food of choice, substrates of carbon and nitrogen, by syringe. The samples were then sealed in glass vials and incubated.

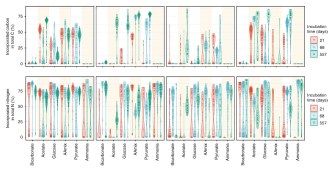

Growth of microbes after being fed carbon (top) and nitrogen (bottom)Image source: Morono, et al

Vials were opened after 21 days, 6 weeks, and 18 months. Stunningly, up to 99 percent of the microbes were revived, even those from the deepest — and thus oldest — cores. Some had increased 10,000 times their number, consuming all of the carbon and nitrogen they’d been given.

The scientists could hardly believe what they were seeing. “At first I was skeptical, but we found that up to 99.1 % of the microbes in sediment deposited 101.5 million years ago were still alive and were ready to eat,” recalls Morono.

“It shows that there are no limits to life in the old sediment of the world’s ocean,” says D-Hondt. “In the oldest sediment we’ve drilled, with the least amount of food, there are still living organisms, and they can wake up, grow and multiply.”

Some have suggested that the microbe may be more recent descendants of their 100-million-year-old ancestors, but D’Hondt says there isn’t enough in the way of nutrients or energy down there to support cell division. That is, unless there’s some other form of energy that has been overlooked, say, some form of radiation. “If they are not dividing at all, they are living for 100 million years, but that seems insane,” he says.