A humpback whale feeding. (Chase Dekker Wild-Life Images/Getty Images)

Baleen whales are heavy drinkers. In just ten seconds, these giant mammals can down over five hundred bathtubs of ocean water, filtering out roughly 10 kilograms of krill in a single swig.

All they have to do is open their mouths and lunge forward at roughly 10 kilometers an hour (6 miles per hour).

The pressure of all that water rapidly hitting a whale’s throat would surely be immense. So how does this group of creatures – which includes right whales, the humpback whale, and the monumental blue whale, amongst several others – make sure their lungs aren’t suddenly flooded with water?

The dissection of several fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) has now revealed a fatty and muscular sac that stops the species from choking. When the whale opens its mouth to feed, this sac swings upwards and plugs the lower respiratory tract.

No such structure has ever been identified in any other animal, but the authors suspect it is probably present in other lunge-feeding whales (called rorquals), like humpbacks and blue whales.

“There are very few animals with lungs that feed by engulfing prey and water, so the oral plug is likely a protective structure specific to rorquals that is necessary to enable lunge feeding,” explains zoologist Kelsey Gil from the University of British Columbia, Canada.

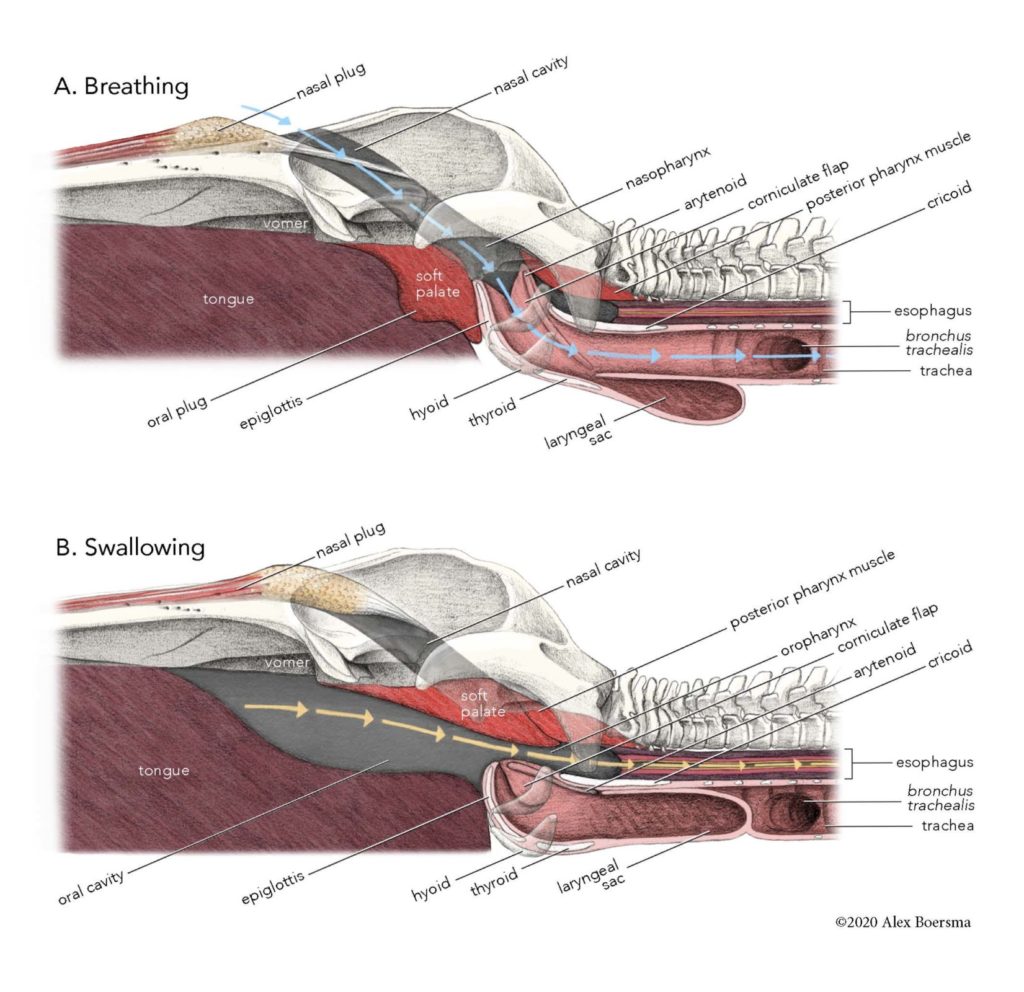

While Gil and her colleagues have not seen the oral plug in action, based on its structure, they think it functions sort of like a railroad switch. When a whale breathes, the plug pops out and opens up the lower respiratory tract. But when a whale feeds, the plug completely blocks off this pathway.

In humans, a flap of tissue known as the epiglottis, covers the path to the lungs when we are eating so we don’t accidentally inhale our food.

But whales have very different ways of eating and breathing. When they are breathing through their blowholes, the fatty plug attached to the soft palate keeps water in the mouth from flowing into the lungs.

When they are eating, however, this fatty plug has to swing up and back, shutting off the path to the whale’s upper blowhole, while opening up the esophagus for swallowing.

Meanwhile, the sheer force of incoming water pushes the whale’s tongue right back against the epiglottis, sealing the lower airway as well.

“It’s kind of like when a human’s uvula moves backwards to block our nasal passages, and our windpipe closes up while swallowing food,” says Gil.

But unlike the throat structures in humans, the ones in whales have to work under great pressure.

“Bulk filter-feeding on krill swarms is highly efficient and the only way to provide the massive amount of energy needed to support such large body size,” explains zoologist Robert Shadwick, also from the University of British Columbia.

“This would not be possible without the special anatomical features we have described.”

After all, it takes a lot of energy for a 27-meter-long fin whale to keep swimming.

There’s still so much to learn about these giant creatures and their life under the waves. Like, how do whales blow bubbles? And do they burp or hiccup?

The authors of the current study would love to watch a baleen whale eat and breathe in real time; to do that, they would need to create a swallow-able camera.

In the meantime, the dissections were not done on whales caught for scientific purposes, but performed on specimens acquired from a commercial whaling operation in Iceland in 2015 and 2018, where fin whales have thankfully not been killed in the past few years.